Introduction

In terms of overall greenhouse gas emissions (GHG), the forest, land use and agriculture (FLAG) sector represent approximately 22% of net anthropogenic GHG emissions, with about half of that coming from agriculture. However, FLAG can contribute an outsized 37% of emissions mitigation by 2030 and 20% through 2050.1 The global food system accounts for nearly one-third of global GHG emissions2 and is responsible for more land use change–a key contributor to GHG emissions–than any other industry.3 The risks to food, feed, and fuel system security from climate change, soil degradation, and compounded rural economic strain are growing. Enterprises, consumers, investors, and shareholders alike increasingly demand more environmental responsibility (see Appendix A of this guide for more details).

Climate and carbon commitments from companies and countries are surging, with more than 700 of the world’s largest publicly traded companies now establishing net zero targets, up from 417 in December 2020.4 While commitments are easy to voice and print, bringing them to life is much more difficult. Sixty-five percent (65%) of corporate targets do not yet meet minimum procedural reporting standards.5 Reporting complete data has been especially challenging for companies that source from agricultural land in their supply chain.6 This challenge is critical to address for these companies to reach net-zero, as these emissions represent about 90% of the carbon footprint of many retail and food producers.7 Organizations require creativity, scale, and incentivization to influence the emissions of upstream or downstream suppliers.

Addressing consumer and shareholder concerns and bringing climate commitments to life will require a shift in the understanding and practice of agricultural production toward more regeneration and sustainability.8 Understanding emerging GHG reporting and target-setting standards have a vital role in boosting transparency, ensuring confidence in reporting, and producing meaningful outcomes toward achieving Scope 3 goals.

In this eBook, we will cover:

- Why the Majority of Reported Agricultural Emissions are Scope 3

- Background on Scope 3 Emissions

- Where does Farming Fit in Scope 3 Emissions Reduction Practices, Programs, & Protocols?

- The Net-Zero Journey of the Agricultural Supply Chain

- The Importance of Programs to Bring Scope 3 Goals to Life

- Accelerating Scope 3 Decarbonization Goals with CIBO Impact

- Climate Risks and Demand for Regenerative Agricultural Practices

Share the Knowledge of Scope 3 Reduction

Corporate Commitments and New Standards for Agricultural Reductions

Over 500 companies with agriculture as a material emissions source in their supply chains have engaged with the Science Based Targets Initiative (SBTi).9 68 of the top 100 companies in the food and beverage sector have existing GHG emission reduction targets.10 Two-thirds of the S&P 500 have set emission reduction targets of some kind.11 Meanwhile, complementary but independent initiatives like the Amazon Climate Pledge and Walmart’s Project Gigaton Initiative are setting a standard for supplier reporting to retail channels. The Climate Pledge now has more than 300 corporate signatories who all agree to measure and report on GHG emissions regularly, decarbonize in line with the Paris Agreement, and remove remaining emissions with real (i.e. verified) offsets to achieve net-zero status by 2040.12 4,500 of Walmart’s suppliers have signed on to reduce or avoid 1 billion tons of carbon emissions from their supply chain by 2030.13

To reach these targets, consumer, investor and, increasingly, regulatory expectations are that the metrics and methods used to measure and report progress towards these goals are all reported in a regular, transparent, and more standardized way. Yet, despite an overall corporate willingness to invest and commit to climate initiatives, a clear process to meet these commitments is still emerging as voluntary or regulator reporting standards continue to develop.

Voluntary Standards

The primary standard of reporting on agricultural emissions is the Greenhouse Gas Protocol (GHGP) Land Sector and Removals Guidance. This guidance is still in draft form and final release is slated for 2023. The standard is already being piloted. Most companies already report their GHG emissions following the GHGP base standards for corporate GHG inventories (Scopes 1 + 2), Scope 3, and additional agricultural guidance. More companies than ever are also reporting their GHG emissions through standards that are based on GHGP principles such as Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), the Task Force on Climate Disclosure (TFCD) recommendations, SASB, or CDP, in addition to the supply chain programs offered by companies mentioned above.

To support transparent, streamlined, and verifiable reporting to reach GHG reduction targets, organizations like SBTi have emerged. Many companies that source from agriculture today have existing targets established with SBTi, and will update those targets by the end of 2023 or 2024 in accordance with the updated guidance released in September 2022 for the Forest, Land and Agriculture (FLAG) sector, developed to help support land based target setting. Corporates wanting to reach FLAG targets will need to follow the drafted GHGP Land Sector and Removals Guidance.

Given current supply chain hurdles in reducing and reporting detailed scope 3 agricultural emissions, additional standards that build on GHGP processes have emerged to propose a solution. These solutions include the Value Chain Initative’s (VCI) Intervention Guidance, which focuses on establishing a new supply shed approach to enable, measure, and report on scope 3 reductions on an annual basis.

All these standards inter-relate to build a voluntary reporting and decarbonization framework for companies that source agricultural commodities.

Proposed SEC Regulations

In the U.S. in 2022 there are currently proposed regulations from the SEC covering Scope 1, 2 and 3 reporting. However, these proposed regulations are not compulsory, and they may never become so. Of the three scopes, Scope 3 is only lightly addressed in the proposed regulations, and then only for very large public companies. Individual farms and ranches are likely to remain unaffected because, typically, they are neither very large nor public, but the companies that source from them will be included. The SEC’s proposal would not require all public companies to disclose their Scope 3 emissions. Among large companies, only those with at least $75 million in equity shares available to the public would be required to disclose their Scope 3 emissions. And that is only if those emissions are significant or if the company has committed to reducing its Scope 3 emissions.14 For large, public organizations with agriculture in their supply chain, the rules, if enacted, still provide great latitude in reporting, allowing “…industry averages and other data to estimate emissions associated with their suppliers, rather than obtain that data from each supplier. And if companies’ estimates are wrong, the proposed rule would shield them from liability.”15

Share the Knowledge of Scope 3 Reduction

The Majority of Reported Agricultural Emissions are Scope 3

Background on Scope 3 Emissions

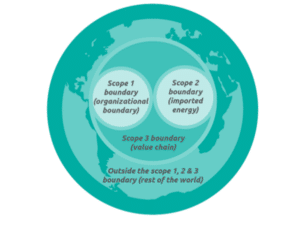

Scope 3 emissions are defined as a company’s indirect GHG emissions up and down the supply chain from where they sit. This includes the GHG emissions impact of products purchased upstream, like ingredients for food, feed, fiber and fuel products. It also encompasses how downstream products, such as farming inputs and implements, contribute to emissions and how they are processed at end-of-lifed.

Image Source: Greenhouse Gas Protocol Land Sector and Removal Guidance.

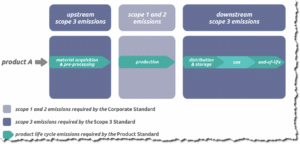

The Greenhouse Gas Protocol Corporate Value Chain (Scope 3) Standard details how Scope 3 emissions are reported across 15 categories.16 There are eight upstream categories and seven downstream categories. Upstream emissions are indirect emissions related to purchased or acquired goods and services. Downstream emissions are indirect emissions related to sold goods and services.17 Not every category will apply to all organizations, and often some categories are excluded from inventories (with provided justification).

Image Source: Greenhouse Gas Protocol.

The Upstream Scope 3 Categories are:

- Purchased goods and services

- Capital goods

- Fuel and energy related activities not included in Scope 1 or Scope 2

- Upstream transportation and distribution

- Waste generated in operations

- Business travel

- Employee commuting

- Upstream leased assets

The Downstream Scope 3 Categories are:

- Downstream transportation and distribution

- Processing of sold products

- Use of Sold Products

- End-of-life treatments of sold products

- Downstream leased assets

- Franchises

- Investments

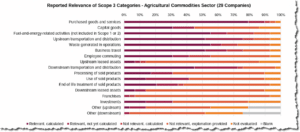

CDP guidance18 on Scope 3 relevance by sector identifies the following GHG Protocol categories as most relevant to the Agricultural Commodities sector:

- Category 1: Purchased goods and services

- Category 10: Processing of sold products

- Category 11: Use of sold products

To identify this list CDP surveyed a number of companies on the relevance of Scope 3 categories to their industry. Seventy-nine percent (79%) of agricultural commodities companies identified Category 1 as relevant and calculated, saying that it is relevant to calculate upstream emission from feed production and fertilizer production. Examples are feed and biofuel companies, food companies with agriculture in their upstream, and apparel companies sourcing cotton.

For these companies, Category 1: Purchased Goods and Services is an obvious fit. The GHG Protocol defines this category as “Extraction, production, and transportation of goods and services purchased or acquired by the reporting company in the reporting year.”

Food-related companies like processors and CPGs are identified as sources of post-production emissions for the agricultural commodities sector. For this reason, Categories 10 and 11 are relevant to food companies but potentially less so to the direct agricultural production (farming) enterprises.19

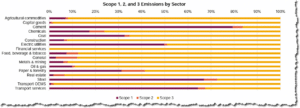

Image source: CDP Technical Note: Relevance of Scope 3 Categories by Sector, April 2022, pp.7.

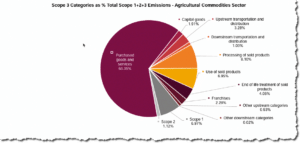

Overall, in the agricultural commodities sector, Category 1 of Scope 3, Purchased Goods and Services, was identified as consuming over 63% of all emissions for Scopes 1, 2 and 3.

Image source: CDP Technical Note: Relevance of Scope 3 Categories by Sector, April 2022, pp. 9.

Where does Farming Fit?

Most of the agricultural commodity supply chain GHG emissions occur on the farm (or in manufacturing goods used on the farm, such as fertilizer). Of the emissions generated by food systems, most—over 80 percent—stem directly from agricultural production and its associated land-use change.20 When companies involved with agriculture are evaluating their net emissions, their indirect, Scope 3 emissions from agriculture represent the lion’s share of their total emissions footprint and opportunity to achieve targets. Because of this, companies who focus on tracking, measuring, reporting, and reducing on-farm Scope 3 emissions can have more impact on overall emissions than if they only focus on other factors under their control like energy efficiency in manufacturing facilities.21 The opportunity to deliver bigger carbon and climate impacts with confidence is substantially greater when reporting on Scope 3 emissions up to and at the farm gate.

Image Source: CDP Technical Note: Relevance of Scope 3 Categories by Sector, April 2022.

In terms of overall greenhouse gas emissions, the forest, land use and agriculture (FLAG) sector represents approximately 22% of net anthropogenic GHG emissions, with about half of that coming from agriculture. However, FLAG has the opportunity to contribute an outsized 37% of emissions mitigation by 2030 and 20% through 2050. Thinking just about Scope 3 emissions, these represent an oversized proportion of emissions for companies with agriculture in their supply chain, accounting for more than 90% of a packaged food company’s total emissions on average, according to research from global Ag Lender Rabobank.23

When companies involved with agriculture are evaluating their net emissions, their indirect, Scope 3 emissions from agriculture represent the lion’s share of their total emissions footprint and opportunity.

In the US, across all economic sectors, Scope 3 emissions are estimated to account for 74% of total emissions, while, for companies operating in the food and beverage sector, an estimated 75-90% of a typical food product’s carbon footprint occurs in the supply chain upstream of the point of sale. The failure of most top food and beverage companies to adequately monitor, disclose on, and reduce Scope 3 emissions from agriculture poses substantial material risk, particularly in light of the growing necessity to assess and address threats and opportunities in exposure to the impacts of climate change, and increasing stakeholder demand for greater corporate transparency on ESG principles.24

In agriculture, Scope 3 emissions from crops are measured as the absolute (total) emissions as well as the carbon intensity, or emissions factor of the yield (emissions per unit crop). Reductions of emissions in the supply chain and across the supply shed from which a business source (upstream) or to which it delivers (downstream) its products demonstrate progress towards carbon-neutral and carbon-negative goals. Reporting on the total emissions of the farming practices and carbon intensity of yields are often challenging tasks. The evolving standards also require categorizing the different emissions sources as detailed by the GHGP rationale provided below:

An important distinction for [emissions in] the agricultural sector is between mechanical and non-mechanical sources. This is because agriculture relies on biological systems, whose emissions or removals of GHGs generally occur through much more complex mechanisms than the emissions from the mechanical equipment used on farmland. Non-mechanical sources are either biological processes shaped by climatic and soil conditions (e.g., decomposition) or the burning of crop residues. They are often connected by complex patterns of N and C flows through farms. Non-mechanical sources emit CO2, CH4 and N2O (or precursors of these GHGs) through different routes. CO2 fluxes are mostly controlled by uptake through plant photosynthesis and releases via respiration, decomposition and the combustion of organic matter. In turn, N2O emissions result from nitrification and denitrification…and CH4 emissions result from methanogenesis under anaerobic conditions in soils and manure storage, enteric fermentation, and the incomplete combustion of organic matter. Mechanical sources are equipment or machinery operated on farms, such as mobile machinery (e.g., harvesters), stationary equipment (e.g., boilers), and refrigeration and air-conditioning equipment. These sources emit CO2, CH4, and N2O, or HFCs and PFCs, and their emissions are wholly determined by the properties of the source equipment and material inputs (e.g., fuel composition).25

GHG Scopes 101 Guided Learning Path

CIBO Technologies has put together a detailed GHG Scopes 101 Guided Learning Path to help people better understand Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions. This curated set of content helps users understand the difference between the scopes and how to evaluate and report on them. Users can embark on this path to gain the knowledge they need to start understanding and offsetting their business’s greenhouse gas emissions. Use this pathway to fast-track your knowledge of key terms, concepts, and differences between Scope 1, Scope 2, and Scope 3 emissions.

Scope 3 Emissions Reduction Practices, Programs, & Protocols

While GHGP and SBTi help companies set their Scope 3 emissions targets, they do not prescribe the exact practices, methods, or programs that companies can use to achieve their goals. SBTi specifically recognizes that “SBTi FLAG helps companies set their overall sector-based reduction target, but companies have the flexibility to choose the most relevant mitigation options to meet their target.”26

Nevertheless, SBTi recognizes that “Agriculture, forestry and other land uses (AFOLU) are both a major driver of global greenhouse gas emissions and an important carbon sink. . . Agricultural commodities represent a significant share of land use. Most of these emissions and removals are related to how land is managed (e.g., fertilizer use and tillage) and how land use is changed over time. . . [emphasis added].”27

Furthermore, SBTi recognizes that locally determined farming practice will vary across geographies and regions to increase organic material in the soil, often referred to as removals, to achieve emissions reductions targets.

“Cumulative removals in agriculture land [come] from enhance[ments] in soil carbon sequestration* from erosion control, use of larger root plants, reduced tillable, cover cropping, restoration of degraded soils and biochar amendments.”28

This is the first time removals have been allowed to be considered within the scope of an overall emissions reduction target. SBTi recognizes this in their guidance;

SBTi references the Project Drawdown Regenerative Annual Cropping Study for estimating the impact that regenerative agriculture practices reliably have on emissions avoidance, reduction and CO2e soil sequestration.29 Project Drawdown30 defines regenerative agricultural practices as:

. . . crop rotation, cover cropping, and reduced tillage to reduce emissions and sequester greenhouse gasses while producing annual crops such as wheat and maize. This solution replaces conventional annual cropping systems. The three key elements of conservation agriculture are minimizing soil disturbance, protecting soil with vegetation, and varying crops from year to year. Because conservation agriculture not only reduces greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere but also makes land more resilient to climate-related events such as long droughts and heavy downpours, it is doubly valuable in a warming world.

Share How to Gett Started on Your Scope 3 Journey in Agriculture

Decarbonizing the Supply Shed

Where the supply chain represents the upstream and downstream members associated with an organization, a supply shed is the greater region where some or all the members of the supply chain exist. For example, upstream farms supplying grain to an ethanol producer may all exist within 100 miles of the ethanol plant. That geography, described by a circle with a 100-mile radius extending out from the plant, is a supply shed. Each ethanol plant managed by a company may have its own supply shed. A supply shed may be a county, a state, a watershed district, or an area described by a bespoke boundary, as in the ethanol plant example. Not every farm inside a supply shed will be part of the supply chain. Using our ethanol plant example, while the farms that supply corn to the plant exist within that 31,400 square mile supply shed, there are other operations as well. Some farms may be in a soybean/corn rotation and only supply corn in alternating years. Some farms may grow wheat and sunflowers. Others may have dairy operations. Just like drawing down CO2 and reducing GHG emissions helps the global climate, so do the regenerative practices by some farms in a supply shed help reduce the overall carbon footprint of the entire supply shed.

The Value Change Initiative defines the supply shed concept as:

A group of suppliers in a specifically defined geography and/or market (e.g., at a national or sub-national level) providing similar goods and services that can be demonstrated to be associated with the company’s value chain. It may not be feasible to demonstrate which specific suppliers provide the goods and services, but it should be demonstrable that they are in the group that do, for example by demonstrating that these suppliers provide material to the company’s direct suppliers. The concept of Supply Shed is introduced to cater for situations where a reporting company may not be able to directly trace sourcing to a specific supplier in the upstream supply chain, but it is known that sourcing comes from that group of suppliers.31

Supply sheds allow reporting companies to account for interventions and programs taken within their supply chain for which there may be limited or no direct traceability. In this way, enterprises can track emissions factor reductions in a supply shed that houses diverse, diffuse, and distributed operations.

Supply shed-based metrics provide an important level of visibility against which year-over-year progress may be measured, especially as individual suppliers change within the geography of a supply shed. To report on Scope 3 emissions across a supply shed with confidence, there is an absolute necessity for companies to have access to detailed seasonal carbon footprinting and carbon intensity calculations.

Share How to Gett Started on Your Scope 3 Journey in Agriculture

The Net-Zero Journey of the Agricultural Supply Chain

When it comes to the achievement of carbon, climate, and Scope 3 goals, corporate desire and commitment are present. However, measuring and reporting are consistently two of the biggest blockers to companies achieving their climate target. Without confidence in metrics and the ability to quantify and report them at scale, progress against emissions reduction goals stagnates. As progress stagnates, analysis paralysis sets and corporate alignment falters.32 The good news is that reliable way-points are emerging for companies on the journey to net-zero. These way points are:

- Inventory corporate emissions sources

- Report emissions

- Set reduction targets

- Reduce emissions through direct land management and supply shed programs

- Offset remaining residual emissions

Step 1 – Inventory Corporate GHG Emissions Sources

Companies get started by establishing an inventory boundary. This often involves engaging with internal subject matter experts or consultants with expertise in GHG accounting. An inventory boundary is the geographic boundary describing the location of all the emissions sources they will calculate. For agricultural-related companies, the inventory boundary for the commodities they source is either at a field (if they source from the same fields every year) or a supply shed level. One of the most critical factors to establish a boundary is the concept of “traceability”. In agricultural systems, traceability means that a company has confidence that their upstream or downstream emissions are attributable to the yield, operations, and practices of a particular farm, field, or parcel, in a given year.

Some companies may own, operate, or contract with the same farms each year. In these cases, the supply chain is well known, and emissions are directly attributable to operations on those fields. The emissions are traceable. However, because many growers rotate crops, shift fields and field boundaries, and alter practices, a company may regularly source from a region – like a county, state, or watershed district, but from different growers in that region. In this case, companies do not have traceability to the growers in their supply chains, rather they have traceability only to the region or “supply shed”. Fortunately, GHGP and VCI guidance help companies establish a sourcing region or “supply shed” from which they source. Supply shed approaches enable companies to deliver traceable Scope 3 emissions calculations from bounded geographies when individual farms, fields and operations are unknown.

For example, if a company doesn’t purchase corn from the same farms every year, but they do purchase all of their corn from a single grain elevator, and that elevator sources from farms in a 50-mile radius, that circle would be that company’s inventory boundary for corn. Companies would repeat this process for all the commodities they source from, and also include additional emissions sources in their comprehensive inventory boundary. For commodities, while it may be tempting to simply define an inventory boundary that is very large (e.g. the U.S. grain belt), the larger the region, the more dilute the emissions quantification and impact will be. Companies should define the smallest practical emissions boundary for each center of operation, but no smaller.

Once inventory boundaries are defined, companies establish an emissions calculation approach. Through this effort, the key emissions sources are categorized, within each inventory boundary, by source and scope as defined by the GHGP Corporate Reporting and Scope 3 standards.33, 34 Supplemental Agricultural Guidance and the draft Land Sector and Removals guidance provide additional detail for accounting and reporting the emissions of agricultural commodities.35, 36 It is important to note that companies following the Land Sector and Removals guidance must inventory their Scope 3 emissions, unlike other sectors where this reporting is optional per GHGP – this is due to the magnitude of Scope 3 emissions compared to the overall carbon footprint of companies that source from agricultural land. Inventories are conducted annually using calendar or financial year approaches.

Step 2 – Report Emissions

Once an inventory is complete, many companies report the outcomes to regulatory or voluntary carbon programs. Employees, stakeholders, investors, and partners are increasingly requiring emissions and reduction progress reports. Many of the largest companies today report their annual emissions in the yearly climate questionnaire to CDP in addition to reporting information in annual ESG reports following GRI38 standards. Depending on the company, it can be essential to ensure carbon intensity metrics of products are also shared with downstream partners, shareholders, or consumers.

Step 3 – Set Reduction Targets

After a company reports their emissions (or sometimes as they are reporting or the first time) GHG targets may be considered and discussed. GHGP offers guidance on establishing a GHG target for agricultural emissions in the draft Land Sector and Removals Guidance (available for download upon request at GHGprotocol.org/land-sector-and-removals-guidance). SBTi recently established their FLAG Guidance to enable companies in the land sector to reach near term (5 to 10 year) GHG reduction goals that can help keep global warming to 1.5 degrees celsius.39 Companies can also establish long-term net-zero goals with SBTi.40

Setting a target requires a company to establish a “baseline” year or period. A baseline year is an inventory year that is compared to future inventory years to demonstrate GHG reductions. In agriculture, emissions may vary widely from year to year. Crop rotation, tillage practice, cover-cropping, and climatic factors all come together in a bio-dynamic system to create variations in emissions. Because of this, GHGP recommends that agricultural systems baselines for Scope 3 reporting be more than just a single year and include a representative period or group of years. In this way, crop rotations, practices and yields will balance to create a representative baseline to evaluate annual progress.

Scope 3 reporting for agricultural systems must consider the diversity and distribution of emissions across not only geographies but also seasons. Soybeans will have a different carbon and emissions footprint than corn. Other crops will differ as well, from wheat, sunflowers, rice, cotton, or oats; each may be grown in the same field over several seasons under a sustainable and regenerative practice regime. These are just some challenges that the draft FLAG and land sector guidance are seeking to address.

Step 4 – Reach Reduction Targets Through Direct Land Management and Supply Shed Programs

Emissions inventory methodologies should reflect the outcomes that incentive programs have on the adoption of sustainable practices by growers in a company’s supply chain.

Regardless of the traceability, companies may request, incentivize or compel practice changes in those fields and with those farmers to enable the adoption of regenerative practices to achieve reduction targets. Regenerative practices such as cover-cropping, no-till, crop rotations, and nitrogen reduction have been proven to help reduce GHG emissions and sequester CO2e in and under the soil. Companies that have full visibility and traceability at the farm level – because of vertically integrated supply chains and/or wholly-owned farmland, the approach to defining and delivering emissions reduction programs will be different than companies that are using a supply shed approach. Organizations that own their own farming land and operations can simply decide to implement emissions reducing programs and direct their grower-employees to perform the practices. Organizations that source from independent growers, co-ops, elevators, and distributors must create programs that offer incentives to adopt the emissions reducing programs. Then they must engage growers, prove the value of the program, and facilitate enrollment in such a way that it neither disrupts nor interrupts growing operations.

Approaches to measure the annual impact of carbon emissions of agricultural land are varied and some are limited when it comes to showing annual improvements while also meeting GHGP and SBTi FLAG requirements. GHGP defines these methods as Tier 1, 2, or 3 approaches based on complexity (adapted from GHGP discussion and International Panel on Climate Change definitions):

- Tier 1 Approaches – emissions estimated with global default emission factors (tonnes carbon per ton commodity). These are coarse and have a high level of uncertainty, these may also not reflect year over year change in carbon intensity. An example would be the average carbon intensity of a ton of corn in the entire United States (this method is used by many companies today and is often derived from detailed Life Cycle Assessment Databases or International Panel on Climate Change data).

- Tier 2 Approaches – emissions estimated with geographically-specific emission factors informed by land management practices of a given region with lower uncertainty ranges.

- Tier 3 Approaches – directly monitored emissions through actual measurements or modeled values derived from actual measurements.

Tier 3 approaches to Scope 3 agricultural emissions that include models most effectively measure the annual impact of adopted regenerative practices at scale. Tier 3 approaches deliver the best and most confident visibility into annual emissions reductions and removals as they can measure and apply uncertainty to annual changes at the farm, field, or a supply shed levels while delivering insights at scale.

Companies with a supply shed boundary need to evaluate the annual emissions factors of their supply shed (emissions impacts of the yield from that land). Companies must also account for the interventions to adopt regenerative agriculture programs on individual farms within that supply shed as demonstrated in VCI Guidance. Draft GHGP guidance requires companies to also monitor soil carbon increases that are counted towards their SBTi FLAG goals. This is because it is possible for some percentage of sequestered, soil-based carbon to be re-emitted to the atmosphere when practices like deep-tillage or decompaction are used after a period of carbon storage in the soil. Soil-based carbon sequestration is a very good outcome of regenerative and sustainable practices; Yyet, confident accounting is necessary in order to accurately account for any future reversals.

Step 5 – Offset Remaining Emissions

Offsets like carbon credits cannot be used to achieve SBTi FLAG targets. Instead, according to guidelines, carbon offsets are intended to be used to neutralize residual and remaining emissions. These are emissions that are unavoidable after reducing a company’s carbon footprint and carbon intensity as much as possible (within reason).

To reach net-zero goals companies may have to neutralize their residual emissions each year with offsets.

Challenges to Measuring Scope 3 Emissions Reductions at Scale

When evaluating emissions from agricultural operations across a large corporate supply chain, the challenge of scale quickly becomes apparent. Agricultural supply chains are distributed, diffuse, and diverse. Supply sheds are large and can be highly distributed across geographies. An organization can purchase goods and services (Scope 3, category 1) in the form of grains from a producer, distributor, or aggregator (e.g., grain elevator or wholesaler) who has sourced that grain from many growers. While on-farm and on-supply-shed emissions factors are monitored, verified, quantified, and reported on each year, complicating Scope 3 accounting is that the grains that ultimately make it into food, feed, and fuel may be mixed across different crop years. Scope 3 solutions must have the ability to engage, enroll, monitor, quantify, verify, and report on operations across a highly distributed network of grower-suppliers.

Agricultural supply chains can be diffuse, with downstream buyers purchasing and contracting grain from a relatively small percentage of acres across multiple supply sheds; thus changes at the field level can be hard to detect if only measuring a supply shed. While we can report at the program level, without a clear system to “mask out” existing farms enrolled in offset or Scope 3 reduction programs, supply shed measurements may result in double counting. A harmonized supply shed and intervention approach is required in order to demonstrate reportable progress for single companies on regenerative acres they incentivize, while still accounting for the carbon intensity of the remaining supply shed acres.

While there is a desire to have traceability to the field level for all companies who source agricultural commodities, the reality is agricultural supply chains are diverse. With modern crop rotations, double cropping, and intercropping. Agrower may plant corn with a wheat cover crop one year and then soybeans the next year, they may plant a cash crop every other season, or two cash crops at the same time.. There are many different variations and permutations to this cycle. Each combination of crop, practice, soil, and climate will have a unique carbon footprint in each season. Organizations must have visibility into the carbon intensity of the commodity crop in the year it was grown, not just in the year it was purchased. Furthermore, this visibility should be at the farm, field, and parcel level with roll-up calculation available at the regional, county, state, and supply shed level. Visibility at the farm level is vital, since a farm supplying a company with corn in year one may be growing soybeans in the next year while supplying a completely different company.

As Scope 3 reporting goals shift from simply producing estimates to accounting for outcomes, a scaled platform approach is required. A scaled platform approach that delivers confidence in Scope 3 reporting should combine:

- Established, independently validated scientific models

- Mechanistic crop, soil, yield, and carbon modeling

- In-season monitoring that combines satellite-based remote sensing with proven practice inferences where satellite imagery is not available

- Practice validation that combines remote sensing with on-the-ground validation

- Reporting capabilities that enable detailed visibility at the parcel, field, farm, region, and supply shed level, and user-defined grouping of fields (AKA land portfolios)

- Integrated data feeds for seasonal crop, practice, rotation, weather, and soil condition variability

- Built-in ability to run what-if scenarios and calculations for different crops, cultivars, inputs, conservation practices, weather conditions, etc., and to see the carbon footprint and carbon intensity impact of those what-if scenarios across custom boundaries

Focus on Emissions Sectors

The GHGP helps companies define their Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions calculations, accounting, and reporting. In recognition that industries have vastly different emissions factors, they have developed industry sector-specific guidelines. In September 2022, they published their draft Land Sector and removals guidance. According to GHGP,

The Greenhouse Gas Protocol Land Sector and Removals Guidance explain how companies account for and report the following activities in their greenhouse gas inventories:

- Land management and land use change

- CO2 removals and storage in land, product and geologic carbon pools

- Biogenic products and products derived from technological CO2 removals across the value chain

The new guidance is used by companies to:

- Inform mitigation strategies by understanding the GHG emissions and removal impacts of land management, land use change, biogenic products and other CO2 removal activities

- Set targets and track performance by including the above activities in GHG targets

- Report GHG inventories, including GHG emissions and CO2 removals and report progress toward GHG mitigation goals37

The Role of MMVR Technology in Delivering Scope 3 Reporting with Confidence

Modeling, monitoring, validation, and reporting technology is well-established, regularly improving in scope, scale and capability, and growing in acceptance. Companies can and do estimate absolute or total emissions, yield, carbon intensity, biomass, and other emissions related results today. U.S. government agencies have recognized the acceptability of using modeling and estimates in Scope 3 reporting. Of course, the more granular and accurate the model-based estimates are, the better the impact on the climate and the better the results for reporting companies and their stakeholders.

Both the USDA and the SEC recognize the efficacy of the modeling and estimate approach. As written by the Center for American Progress, according to the SEC’s proposed rule:

. . . [C]ompanies would be free to estimate the Scope 3 emissions of their agricultural suppliers based on other data as long as they disclosed how they developed their estimates, such as by using data on industry averages or input-output models. In fact, companies that currently estimate the Scope 3 emissions of their agricultural suppliers do so using models based on emissions factors, estimates of acreage or cattle head, and other data.42

Similarly, the acceptability of the technology-based MMVR approach is well established at the USDA as well. In 2022, the USDA made over 70 grants totaling more than $2.8Bn under its Partnership for Climate-Smart Commodities program. Of those grant recipients, at least 20% engage technology partners that specifically use MMVR technology to quantify GHG and carbon emissions avoidance, reduction, and sequestration. These are the same types of practices and results that contribute to Scope 3 reporting, programs, and results.

The Importance of Programs to Bring Scope 3 Goals to Life

Programs focused on growers and agricultural supply chains are vital for achieving Scope 3 goals. According to the EPA: “. . . [B]ecause scope 3 emission sources may represent the majority of an organization’s GHG emissions, they often offer emissions reduction opportunities. Although these emissions are not under the organization’s control, the organization may be able to impact the activities that result in the emissions. The organization may also be able to influence its suppliers or choose which vendors to contract with based on their practices [emphasis added].”43

Similarly, as far back as 2018, SBTi was recommending organizations start and support supplier emissions reduction programs and use platforms that facilitate supplier engagement and data collection to run programs consistently and at scale.44 More recently, influencers and authorities in regenerative agriculture have outlined the need for incentive-based programs. Led by businesses focused on reducing their Scope 3 emissions across their agricultural supply chains and sheds, programs that combine regenerative farming financing, practice transition assistance, pay-for-performance, and pay-for-practice are shown to deliver quantifiable carbon footprint and carbon intensity reductions.45 Investors are getting on board as well. Director of shareholder advocacy at Trillium Asset Management Kate Monahan spoke on the importance of Scope 3 programs and platforms that engage growers across the food industry, saying:

A focus on procurement and supplier engagement needs to be a major component of food companies’ transition plans. One thing we’re seeing right now is companies launching pilot programs with their suppliers. Many investors want to see potential efficacy, scalability, and the specifics of these projects.

More broadly, is a company enabling the low-carbon transition by providing incentives or helping subsidize the upfront costs associated with various sustainable agricultural methods? If a producer accepts responsibility and makes positive changes, are they rewarded with preferential pricing or longer contracts? Thoughtful approaches can help pilot programs become permanent strategies that support efforts to prove climate-related initiatives are not one-off projects. They can be embedded within the business’ core decision-making processes. The interconnectedness of agricultural risk and the sector’s exposure – and contributions – to climate change are fueling investors’ desire for evidence that companies aren’t throwing darts at climate-related initiatives, but that efforts are strategy-driven and demonstrate diligence in achieving corporate goals [emphasis added]46.

These anecdotes evidence the importance of taking Scope 3, carbon, and climate promises and bringing them to life at the farm-gate. Programs bring climate promises to life. Programs engage growers. Programs incentivize and reward the transition to regenerative farming, which helps cut emissions factors in the upstream agricultural supply chain.

Programs also require a scaled technology platform to run effectively and efficiently at scale. While they can be designed on a whiteboard and trialed with an enterprising project manager and a good spreadsheet, they fail to scale and run efficiently without a purpose-built technology platform. The sheer scope of farmland acres combined with the diversity of crops, practices, and weather require a platform approach, one that can handle programs for both supply chain engagement and supply shed monitoring. The same platform must be able to roll up individual land-based insights into supply shed reports in order to help businesses achieve full visibility on the progress of their Scope 3 projects.

Share How to Gett Started on Your Scope 3 Journey in Agriculture

Accelerating Scope 3 Decarbonization Goals with CIBO Impact

Companies that rely on agricultural products are challenged to develop confident, transparent inventories of their agricultural carbon footprint. They need quantifiable, verifiable methods to account for and claim real reductions to that footprint. Many in the agricultural sector have limited visibility into their agricultural supply-chain. Instead they rely on 3rd party consulting, outdated and coarse data, and ad-hoc reporting.

As we have seen, traditional methods for verifying and reporting disclosures and reductions of these Scope 3 “field to farm-gate” emissions are at the same time overly complex, nebulous, and constantly evolving. That’s where CIBO comes in.

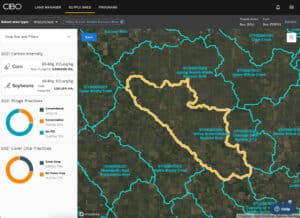

CIBO Impact provides confident upstream and downstream visibility into ag-based Scope 3 emissions, reductions and claims. When considering specific Scope 3 categories, CIBO Impact can help.

- GHG Category 1 (Purchased goods and services): Any organization with agriculture in their upstream can see and report on the carbon footprint of farming practices in their supply chain or supply shed. Additionally, Carbon Intensity of the yield for any given year is also quantified and reported as grams of CO2e per kg of yield. Measurements are reductions from baseline and delivered by the CIBO Impact Platform. What-if scenarios to explore the emissions reduction impact of different practices or weather scenarios are also able to be run through CIBO CarbonLab(™).47

- GHG Category 11 (Use of sold products): Any organization with agriculture and growing operations in their downstream. The GHGP identifies fertilizer companies as an example of a sold product that has a downstream Scope 3 emissions impact.48

- GHG Category 15: Any organization who is investing in agricultural operations, land, or is sponsoring a project or program on CIBO that reduces emissions.49

CIBO Impact is the award-winning, scalable software platform for the creation, management, and verification of nature-based agricultural carbon credits and Scope 3 reduction programs. Companies seeking to decarbonize the supply chain can create and manage incentive programs for farmers growing low-carbon commodities and feedstocks. Whether paying premiums for certified regeneratively-grown products, or creating incentives for growers to adopt new practices, CIBO Impact is the solution for end-to-end program creation and execution.

CIBO Technologies helps companies in the food and agriculture value chain efficiently develop, deliver and scale customized grower-facing emissions reducing incentive programs. CIBO does this by leveraging CIBO Impact, the science-based software platform. Programs examples include:

- Carbon credit generation (offsets)

- Scope 3 emissions reduction and reporting

- Premiums on low carbon intensity feedstock

- USDA programs

- Sustainable product incentives

- Sourcing growers for specific crops or practices

CIBO Impact is the only commercially available solution that can manage large-scale regenerative agriculture programs. From grower identification, pre-qualification, and enrollment, to practice verification and monitoring, to quantification and reporting on carbon, CIBO delivers results at scale.

CIBO Impact is a full-stack software solution that provides reliable, efficient Scope 3 accounting and annual reporting for companies within the agri-food chain that are making emissions disclosures and reduction claims. CIBO Impact provides accurate assessment of on-the-ground farm-level practices and their resultant emissions.

CIBO Impact: Farm & Field Supply Chain Analysis

CIBO Impact enables companies to instantly perform field-level assessments for fields and farms enrolled in carbon, emissions reduction, and regenerative ag programs. Companies are able to report with confidence year-over-year and year-over-baseline changes in emissions and practices that are attributable to programs.

Key Capabilities:

- Monitor On-The-Ground Management: Leverage CIBO’s advanced computer vision capabilities to determine the unique management history of individual fields, including tillage, rotation, cover crop and more.

- Perform Field-Level Analysis: Quantify the carbon footprint, carbon intensity and yield potential of fields under actual, farmer-reported and “what-if” management scenarios with easy-to-use calculators.

- Assess Program Eligibility & Enroll: Rapidly assess program eligibility for any field(s) in your growers’ portfolio and enable convenient enrollment.

- Manage Large Portfolios of Fields & Farmers: Organize and search through thousands of fields, farms and growers using our convenient tagging system.

CIBO Impact: Supply Shed Analysis

Perform year-over-year inventories of supply shed-level carbon emissions, reductions/removals, carbon intensity, yield, cash crop, cover crop, and tillage acres. CIBO Impact lets companies perform efficient supply shed-level GHG inventories using the most up-to-date science and technology available, and then report on those inventories in a transparent, audit-ready fashion.

Because reporting and supply sheds will often vary by company, product, and year, CIBO Impact offers flexible reporting options, including:

- Winning SaaS platform user experience in the CIBO Impact application UI

- PDF and CSV export of reports and insights

- API access to CIBO Impact

CIBO Impact supports crops and crop functional groups in our mechanistic, ensemble-based crop models and computer vision AI.

CIBO – Supported Primary Crops:

- Corn, Soy, Wheat, Cotton

CIBO – Supported Crop Functional groups50

- C4 grasses (corn, millet, switchgrass)

- C3 grasses (wheat, rye, oats, barley)

- Legumes (soybeans, field peas, chickpeas)

CIBO Impact delivers confidence in Scope 3 reporting, calculations, benchmarking, and reporting metrics across fields, supply chains, farms and supply sheds. Available metrics include (but are not limited to):

- Carbon footprint of practices on cropland (tonnes of CO2 equivalent/acre/year given specified practices)

- Carbon intensity / emissions factors (grams of CO2 equivalent/kg yield for the year)

- Regenerative Potential (tonnes of CO2 equivalent / acre of the land if regenerative practices were adopted)

- Crop rotation

- Modeled crop yield

- Tillage type

- Cover crop status

Supply Shed Aggregations:

- County, State, HUC watersheds

- User-defined boundaries

Using these metrics from CIBO Impact, enterprises can:

- Understand Emission at the Supply Shed Level: Quantify emissions factors within various geographic boundaries, like, states, watersheds, counties and draw distances, to create supply-shed level metrics.

- Monitor On-the-Ground Activities: Quantify and verify management practices influencing emissions at the field level and aggregate across entire supply sheds.

- Provide Efficient Scope 3 Reporting: Leverage precise annual emissions factors and practice adoption rates to ensure accurate reporting and recognition of emissions, reductions and removals.

- Gain High-Value Insights on Sustainable Supply: Identify regions of high potential for emissions reductions/removal and source from verifiably low-carbon supply sheds.

Scope 3 Programs with CIBO Impact

The integrated CIBO Program Engine equips you to rapidly develop, deliver, and manage all types of practice incentive, regeneration and carbon programs for your growers. Whether reducing Scope 3 emissions, generating carbon offsets, paying for practice changes, or sourcing regenerative grain, the CIBO Program Engine simplifies the process for sponsors and growers alike.

CIBO lets you bring any kind of program to life, with most programs fall into one of 4 types:

- Carbon – Carbon credits, carbon offsets and Scope 3 reductions

- Practice – Paying to adopt new practices such as cover cropping or reducing tillage

- Certification – Certified certified sustainably grown crops

- Grower Recruitment – Sourcing growers who meet specific criteria

Program Capabilities:

- Prequalify land and understand the potential return: Growers and their trusted advisors simply upload field boundaries and answer a few questions to instantly understand their land’s eligibility for incentive programs

- Simplified and accelerated program enrollment: CIBO provides convenient workflows and scaled data to make enrollment fast and painless

- Monitor status and generate income: Growers see more with CIBO, where they can instantly view program and payment status, and get paid as practices and/or carbon are verified

- Automatically prequalify for new programs: As new incentive programs are deployed, fields will automatically run through prequalification

Conclusion

Scope 3 matters to organizations and investors involved with and interested in agriculture. We examined the climate change threat to food, feed, and fuel production systems and the companies that rely on them. We explored the increased demand for transparency, accuracy, and confidence in reporting on sustainability initiatives. We saw how results—not just pledges—matter, and how carbon, climate, and Scope 3 promises made in the boardroom must be brought to life at the farm gate. We saw how the role of ESG as part of corporate responsibility for agriculture-related companies is increasing, and we discussed some of the challenges and requirements of existing and emerging Scope 3 guidelines. We explored the requirements for tracking, monitoring, and reporting on Scope 3 emissions reductions at scale for both supply chains and supply sheds. The special significance of programs as the vehicle to bring climate promises to life was discussed. Finally, we examined the opportunities that the CIBO Impact platform delivers as a complete, scaled software solution for corporate Scope 3 initiatives, grower-focused programs, and complete regenerative agriculture transformations for the supply chain and supply shed.

Even as rules and regulations continue to shift, forward-thinking and climate-conscious companies are expressing their desire to make climate-positive moves in the shift to a zero-carbon economy. It is clear that CIBO Impact is the ideal scaled software solution that can deliver programs, insights, and results that create an impact.

Please contact us to see how CIBO Impact can help you create your impact.

Share How to Gett Started on Your Scope 3 Journey in Agriculture

Appendix A: Climate Risks and Demand for Regenerative Agricultural Practices

The Climate Risk To Growers

It is no secret that agriculture is deeply intertwined with micro, local, and global climate. As global trends drive local extreme weather events, crops and cropping systems are affected. According to NOAA, “Incidents of extreme weather are projected to increase as a result of climate change. Many locations will see a substantial increase in the number of heat waves they experience per year and a likely decrease in episodes of severe cold. Precipitation events are expected to become less frequent but more intense in many areas, and droughts will be more frequent and severe in areas where average precipitation is projected to decrease.”51 These changes are already being witnessed across the U.S.

Over the next 50 years, heavy rainfall is expected to become more intense, with longer dry/drought periods, between rainfalls, creating more flood conditions.52 As extreme climate events increase in frequency, their impact on farming operations and infrastructure also becomes more frequent. Additionally, even for farms and communities that are unaffected by severe but localized weather events, the overall trends will affect yields and predictability. Beyond storms and floods, shifting precipitation, rising temperatures, soil degradation, drought, new pests, pathogens, and weed problems all affect yields and profitability. Volatility in yields and on-farm profitability in turn create increased risk and uncertainty for lenders upon whom growers rely every year for operational loans and capital improvements.

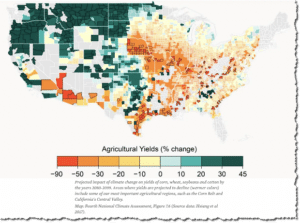

The graphic below53 from the Union of Concerned Scientists USA illustrates the predicted cumulative effects of climate change: accelerated crop failures and yield changes–especially across the grain belt in the U.S.

The Climate Risk To Enterprises

In addition to farmers, enterprises and organizations that rely upon agriculture in their supply chain are left facing these challenges as well. From food, feed, and fuel supply security, to commodity cost increases from depressed yields, to the costs of underutilized infrastructure like bins, barges, elevators, and distribution hubs, increased vulnerability to climate-created damage and inefficient utilization create pressure on organizations to work with growers to mitigate supply chain risks in the short term and remove risk drivers in the longer-term. Additionally, the risk to the economics of rural communities cannot be understated. As rural farming communities experience the front-line harms of climate change, those communities and the incomes they rely upon also dry up. The drought on the land is as bad as the economic drought wrought on communities and capital.

As yields decline, availability of downstream goods decreases and costs go up. This means consumer goods, textiles and biofuels all see price increases, depressing consumption. As risk grows, so does the cost of operating capital; as availability shrinks, it drives consolidation and pushes out businesses and producers with further impacts on rural communities. This in turn further increases the cost to produce raw commodity materials and further drives down yield while simultaneously risking accelerated soil degradation and erosion.

Overall, the global transition to a low-carbon economy is increasingly a key concern for enterprises. But a low-carbon economy cannot be achieved without addressing Scope 3 emissions.54 Enterprise GHG emissions and the GHG emissions of their value chains are at the center of their ability to navigate and accelerate into this change. Those leading the way have the opportunity to both set the pace and influence the standards to which the laggards will have to conform.

The Consumer & Investor Demand For Sustainable Products & Reporting

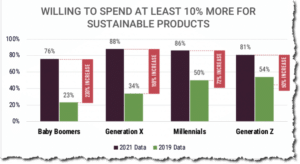

Consumers and shareholders alike are demanding environmental responsibility and expressing greater interest in understanding where and how their products are produced. According to a consumer survey reported on by Forbes: “. . . [C]onsumers across all generations—from Baby Boomers to Gen Z—are now willing to spend more for sustainable products.”55

Even the pressure of high inflation in 2022 is not thwarting consumer demand for sustainable products: “Despite the pressure of high inflation—which has skyrocketed in the US since 2020 (from 1.4 percent to currently 8.5 percent)—66 percent of U.S. consumers and 80 percent of young U.S. adults (ages 18-34) surveyed are willing to pay more for sustainable products versus less sustainable competitors.”56

Unfortunately, a severe gap exists for consumers in their ability to identify sustainable companies and understand how much those companies are doing. “78 percent of those surveyed say that, despite their desire to support companies that align with their values, they don’t know how to identify environmentally friendly companies.”57

Addressing this gap is one of the key capabilities that Scope 3 reporting is designed to address.

Similarly, while perhaps more slowly than their consumer counterparts, business executives are increasingly aware that investing in ESG and working to reorient businesses around a carbon-neutral or carbon-negative economy is the right choice for business. Harvard Business Review finds that, despite challenges, investing in ESG pays off.58 The data is stark, according to Swiss Re Group, that global GDP is expected to take an 18% hit if no climate change mitigation action is taken. That hit impacts 48 countries who collectively total 90% of the global economy.59 Swiss Re is clear in their prescriptions for change, saying: “Mitigating climate change requires a whole menu of measures. More carbon-pricing policies combined with incentives for nature-based and carbon-offsetting solutions are needed, as well as international convergence on taxonomy for green and sustainable investments. As part of financial reporting, institutions should regularly disclose how they plan to achieve the Paris Agreement and net-zero emission targets [emphasis added].”60

Share the Knowledge of Scope 3 Reduction

End Notes

- Forest, Land and Agriculture Science Based Target-Setting Guidance, Anderson, Bicalho, Wallace, Letts, Stevenson, September 2022, pp3. PDF Link: https://sciencebasedtargets.org/resources/files/SBTiFLAGGuidance.pdf

- “Climate Change and Land: an IPCC special report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems.” IPCC, 2020.

- “The global assessment report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services.” IPBES, 2019.

- Net Zero Stocktake 2022, June 2022, https://zerotracker.net/insights/pr-net-zero-stocktake-2022

- Net Zero Stocktake 2022, Ibid.

- Hansen et al., 2022, The status of corporate greenhouse gas emissions reporting in the food sector: An evaluation of food and beverage manufacturers. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0959652622018832

- https://research.rabobank.com/far/en/sectors/grains-oilseeds/carbon-farmers-the-food-system-needs-you-to-clean-up-emissions-for-the-whole-chain.html

- https://www.ceres.org/news-center/blog/qa-food-industry-must-act-scope-3-emissions

- Sum of food, beverage & agriculture, apparel and retail companies with approved SBTi targets and commitments. https://sciencebasedtargets.org/resources/files/SBTiProgressReport2021.pdf

- Reavis et al., 2022, Evaluating Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Climate Mitigation Goals of the Global Food and Beverage Sector https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsufs.2021.789499/full

- Why Companies aren’t living up to their climate pledges, John Goddard, August 2022, https://hbr.org/2022/08/why-companies-arent-living-up-to-their-climate-pledges

- The Climate Pledge announces nearly 100 new signatories, March 2022, https://www.aboutamazon.com/news/sustainability/the-climate-pledge-announces-nearly-100-new-signatories

- https://www.walmartsustainabilityhub.com/climate/project-gigaton

- Alexandra Thornton, The SEC’s Proposed Scope 3 Emissions Disclosure Will Not Affect Farms and Ranches, June 6, 2022, https://www.americanprogress.org/article/the-secs-proposed-scope-3-emissions-disclosure-will-not-affect-farms-and-ranches/

- Ibid.

- Ibid.https://ghgprotocol.org/standards/scope-3-standard

- Ibid.https://ghgprotocol.org/standards/scope-3-standard

- CDP Technical Note: Relevance of Scope 3 Categories by Sector, April 2022, pp.7, https://cdn.cdp.net/cdp-production/cms/guidance_docs/pdfs/000/003/504/original/CDP-technical-note-scope-3-relevance-by-sector.pdf?1649687608

- Ibid.

- https://engagethechain.org/resources/measure-chain-tools-assessing-ghg-emissions-agricultural-supply-chains

- Field to Farm Gate: The most critical piece of Scope 3 emissions for brands that want to reach their ESG goals, Leah Wolfe, September 2021, https://howgood.com/2021-9-23-field-to-farm-gate-scope-3-emissions-esg-goals/

- Forest, Land and Agriculture Science Based Target-Setting Guidance, Anderson, Bicalho, Wallace, Letts, Stevenson, September 2022, pp3. PDF Link: https://sciencebasedtargets.org/resources/files/SBTiFLAGGuidance.pdf

- Deadline 2030: Slashing Value Chain GHG Emissions by a Third, Marjolein Hanssen, September 2021, https://research.rabobank.com/far/en/sectors/consumer-foods/deadline-2030-slashing-value-chain-GHG-emissions-by-a-third.html

- https://engagethechain.org/top-us-food-and-beverage-companies-scope-3-emissions-disclosure-and-reductions

- GHG Protocol Agricultural Guidance, pp 24, https://ghgprotocol.org/sites/default/files/standards/GHG%20Protocol%20Agricultural%20Guidance%20%28April%2026%29_0.pdf

- Forest, Land and Agriculture Science Based Target-Setting Guidance, Anderson, Bicalho, Wallace, Letts, Stevenson, September 2022, pp43. https://sciencebasedtargets.org/resources/files/SBTiFLAGGuidance.pdf

- Forest, Land and Agriculture Science Based Target-Setting Methods Addendum, September 2022, pp 5, https://sciencebasedtargets.org/resources/files/SBTiFLAGMethodsAddendum.pdf

- Ibid. pp 15.

- Ibid. pp 15.

- Conservation Agriculture, https://drawdown.org/solutions/conservation-agriculture

- Value Chain (Scope 3) Interventions – Greenhouse Gas Accounting & Reporting Guidance, V 1.1, May 2021, https://www.goldstandard.org/sites/default/files/value_change_scope3_guidance-v.1.1.pdf

- Why Companies aren’t living up to their climate pledges, John Goddard, August 2022, https://hbr.org/2022/08/why-companies-arent-living-up-to-their-climate-pledges

- https://ghgprotocol.org/corporate-standard

- https://ghgprotocol.org/standards/scope-3-standard

- https://ghgprotocol.org/agriculture-guidance

- https://ghgprotocol.org/land-sector-and-removals-guidance

- Ibid.

- https://www.globalreporting.org/

- Forest, Land and Agriculture Science Based Target-Setting Guidance, Anderson, Bicalho, Wallace, Letts, Stevenson, September 2022, pp6. https://sciencebasedtargets.org/resources/files/SBTiFLAGGuidance.pdf

- https://sciencebasedtargets.org/resources/files/Net-Zero-Standard.pdf

- Value Chain (Scope 3) Interventions – Greenhouse Gas Accounting & Reporting Guidance, V 1.1, May 2021, https://www.goldstandard.org/sites/default/files/value_change_scope3_guidance-v.1.1.pdf

- https://www.americanprogress.org/article/the-secs-proposed-scope-3-emissions-disclosure-will-not-affect-farms-and-ranches/

- https://www.epa.gov/climateleadership/scope-3-inventory-guidance

- How Can companies address their Scope 3 greenhouse gas emissions, Labutong & Hoen, May 2018, https://sciencebasedtargets.org/blog/how-can-companies-address-their-scope-3-greenhouse-gas-emissions

- How to finance Scope 3 emissions reductions on farms, Lieb, February 2022, https://www.greenbiz.com/article/how-finance-scope-3-emissions-reductions-farms

- Q&A: Food industry must act on Scope 3 emissions, Nash, September 2022, https://www.ceres.org/news-center/blog/qa-food-industry-must-act-scope-3-emissions

- https://ghgprotocol.org/sites/default/files/standards_supporting/Chapter1.pdf

- https://ghgprotocol.org/sites/default/files/standards_supporting/Chapter11.pdf

- https://ghgprotocol.org/sites/default/files/standards_supporting/Chapter15.pdf

- Crop functional groups are supported for Verra, CAR, and VCI projects

- https://www.climate.gov/teaching/literacy/7-c-increased-extreme-weather-events-due-climate-change

- Union of concerned scientists, Climate change and agriculture, March 20, 2019, https://www.ucsusa.org/resources/climate-change-and-agriculture

- Ibid.

- Why Companies Should Be Required To Disclose Their Scope 3 Emissions, Alexandra Thornton, December 2021, https://www.americanprogress.org/article/why-companies-should-be-required-to-disclose-their-scope-3-emissions/

- Consumers Demand Sustainable Products and Shopping Formats, Greg Petro, March 2022, https://www.forbes.com/sites/gregpetro/2022/03/11/consumers-demand-sustainable-products-and-shopping-formats/?sh=4b9a27476a06

- Majority of US Consumers Say They Will Pay More for Sustainable Products, Sustainable Brands, September 2022, https://sustainablebrands.com/read/marketing-and-comms/majority-of-us-consumers-say-they-will-pay-more-for-sustainable-products

- The State of Consumer Spending, Gen Z Influencing All Generations to Make Sustainability-First Purchasing Decisions, November, 2021, The Baker Retailing Center at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. https://www.firstinsight.com/white-papers-posts/gen-z-influencing-all-generations-to-make-sustainability-first-purchasing-decisions

- Yes, Investing In ESG Pays Off, Polman, Winston, April 2022, https://hbr.org/2022/04/yes-investing-in-esg-pays-off

- World Economy set to lose up to 18% DGP from climate change if no action take, reveals Swiss Re Institute’s stress-test analysis, April 2021, https://www.swissre.com/media/press-release/nr-20210422-economics-of-climate-change-risks.html

- Ibid.